"Get ready!" you shout. "We're leaving for grandma's house in half an hour."

Your three kids, at three different ages, exhibit three different levels of understanding a concept (i.e., a unit of time).

Your 12-year-old opens his tablet and starts streaming a show that finishes in 22 minutes, confident 8 minutes is enough time to comb his hair and find his shoes. He understood your announcement.

Your 12-year-old opens his tablet and starts streaming a show that finishes in 22 minutes, confident 8 minutes is enough time to comb his hair and find his shoes. He understood your announcement.

Your 7-year-old is less certain and asks, "Dad, is that enough time for pancakes?" You're about to explain how cooking, eating, and clean-up take longer than 30 minutes, when...

Your 4-year-old grabs your hand, pulling you toward the front door, screaming "Yay! Grandma's house!", not understanding she has to wait; you're not leaving right now.

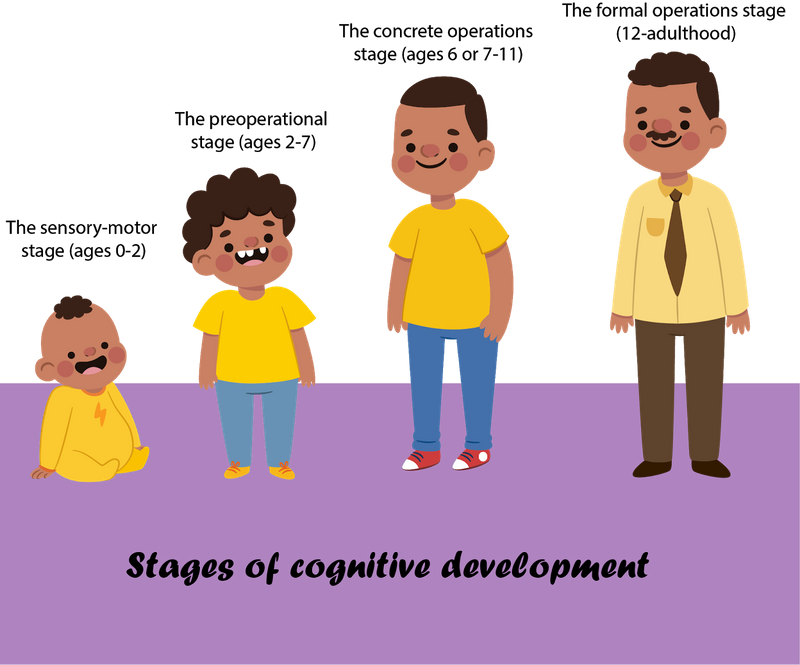

Three different ages, three different levels of understanding. If you've ever noticed children's knowledge gets more accurate and sophisticated with age, you've observed a main principle of Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development.

Piaget's Theory: The Basics

Piaget's theory of cognitive development differed from an earlier belief that children were simply "mini-adults". His research introduced new ideas about how children think and can most effectively be taught:

Children and adults don't think or learn the same way, so children shouldn't be trained as if they were adults.

A developing child isn't just learning new facts but is building a "mental model of the world." This constructivist view says children learn better by doing (active learning) than through lectures (passive learning).

Piaget worked as an IQ test scorer in the 1920s. He used observation and interviews to find out why children of similar ages often made similar errors in their responses to the test questions.

He noticed children’s cognitive processes (thinking abilities) become more complex as they age. His new theory of cognitive development said children’s thinking abilities develop in 4 stages that always follow and build on each other in a specific order:

Click play on the video player above to listen to an accessible audio version of the table.

Sensorimotor Stage (birth to 2 years)

In the first stage of Piaget's theory of cognitive development, the infant starts to construct their understanding of the world by using their physical senses and moving their body to explore their surroundings.

Photo by Jimmy Conover on Unsplash

Photo by Jimmy Conover on UnsplashEarly in the first stage, a baby has no “mental picture” of the world built from memories. Later, toddlers start to store and recall information, leading to object permanence (understanding when a person or object disappears from view, they're still there, as in a game of peekaboo).

The simplest communication and problem solving abilities emerge in the first stage:

Photo by hui sang on Unsplash

Photo by hui sang on UnsplashBabies learn their bodily sounds and gestures can cause things to happen, like crying to get a parent to feed them or grasping at the air to show they want a toy.

Photo by Isabel Lenis on Unsplash

Photo by Isabel Lenis on UnsplashToddlers show the capacity for “symbolic function.” They start to acquire language (understanding a word can stand in for an object) and use their imaginations in pretend play.

Preoperational Stage (2 to 7 years)

In the second stage, children are still unable to perform operational (logical) tasks: "thinking is influenced by the way things appear rather than logical reasoning."

However, basic symbolic function becomes more advanced:

In symbolic play, children pretend one object has the traits of another (for example, pretending their slippery socks are ice skates).

Language expands as children understand more clearly how words stand in for specific objects, people, and ideas.

Abstract representation also improves in this stage as the imagination grows more powerful:

Children's drawing in the preoperational stage “begins as meaningless scribbles and progresses to more accurate representations of people.”

This is also the stage when a child might mention an imaginary friend.

Basic numerical concepts begin to make more sense in this stage. Younger preoperational children understand comparative terms like “more” and “bigger.” Later, they can grasp number, size, and quantity.

By the end of this stage, they have a stored bank of memories that impact thinking and behavior:

Children can tell stories of recalled events, even if they involve people or objects not there at the moment.

They can imitate people, animals, and objects (such as machines) from memory.

Children in this stage still see the world mostly through their own perspective and can't yet grasp how others think.

Quiz

What kinds of behaviors would you reasonably expect to see from a child in the preoperational stage? Select all that apply.

Concrete Operational Stage (7 to 11 years)

Early in the third stage, children learn by encountering "concrete" (real) objects as opposed to “abstract or hypothetical problems.”

Early in the third stage, children learn by encountering "concrete" (real) objects as opposed to “abstract or hypothetical problems.”

Later in this stage, they are better able to perform operations (logical actions) in their minds. For example, they can add mentally instead of counting on their fingers.

General numerical and spatial reasoning improves throughout this stage. Children can now:

Solve basic math problems.

Estimate the length of time it takes to complete a task.

Comprehend measures of distance.

Several new operational (logical) abilities emerge in this stage. Children now understand:

Conservation: A quantity of objects stays the same even if their appearance changes (if they drop some candies from a bag into their hand, the total number of candies is the same as before any candy fell out).

Reversibility: An item can change states, or return to an original stage (imagine a ball of clay being smashed flat, then rolled back into a ball).

Decentering: Multiple traits of an item can be grasped at once, instead of envisioning only one trait (if asked to imagine a stuffed animal, they can picture the size, weight, color, texture, and type).

Identity: A person or object is the same even if the appearance changes (if a parent gets the family car repainted, it’s still the same car).

Children in the third stage start to understand that other people might see things in their own unique way (decanting). They can imagine other people's feelings as their egocentrism (i.e. their own self-interest) decreases.

Quiz

Which classroom subjects or topics might be appropriate for children in the concrete operational stage? Choose all that apply.

Formal Operational Stage (age 12 and up)

Concrete operations are carried out on things whereas formal operations are carried out on ideas. Formal operational thought is entirely freed from physical and perceptual constraints

— Saul McLeod, Ph.D.

In this stage, children grasp more complex logical (operational) rules. They can apply logic to help them:

solve new problems and analyze unfamiliar situations

think in abstractions (solve fraction problems or algebraic equations)

grasp an argument's claims without examples or illustrations

Piaget believed hypothetical-deductive reasoning (a person's ability to use what they’ve already learned to create new theories about what could or might happen) emerged in this stage. An older child with this ability can:

Piaget believed hypothetical-deductive reasoning (a person's ability to use what they’ve already learned to create new theories about what could or might happen) emerged in this stage. An older child with this ability can:

imagine different outcomes for a complex scenario or situation

engage in scientific reasoning and hypothesizing

understand different political and ethical points of view

At the fourth stage, a child can think critically about themselves and change their behavior with respect to others. Children with this ability can:

understand why arguments happen with friends or family members

decide what part they played in the conflict

respond rationally to repair the conflict

Critics of Piaget’s theory of cognitive development argue not everyone develops hypothetical-deductive reasoning skills, even by adulthood:

Critics of Piaget’s theory of cognitive development argue not everyone develops hypothetical-deductive reasoning skills, even by adulthood:

40-60% of college students fail at formal operational tasks, and...only one-third of adults ever reach the formal operational stage. Because Piaget concentrated on the universal stages of cognitive development and biological maturation, he failed to consider the effect that the social setting and culture may have on cognitive development.

Take Action

Learn more about Piaget's theory of cognitive development can impact learning!

Your feedback matters to us.

This Byte helped me better understand the topic.