This logo isn't an ad or affiliate link. It's an organization that shares in our mission, and empowered the authors to share their insights in Byte form.

Rumie vets Bytes for compliance with our

Standards.

The organization is responsible for the completeness and reliability of the content.

Learn more

about how Rumie works with partners.

When we think about how things are designed from an accessibility lens, often many learners or users are left out.

How would your life be impacted as a learner if you couldn't hear? What would be helpful?

In this situation, clear-plastic face masks are a great tool for more accessible learning.

Create a more accessible space to make sure all your learners fully benefit from your learning content!

Did you know?

Specific learners may need accommodations. Always refer to a learner's official accommodations list that you receive from your disability services center and make the appropriate adjustments to your learning designs. Remember to keep this information confidential.

Why is accessible design important?

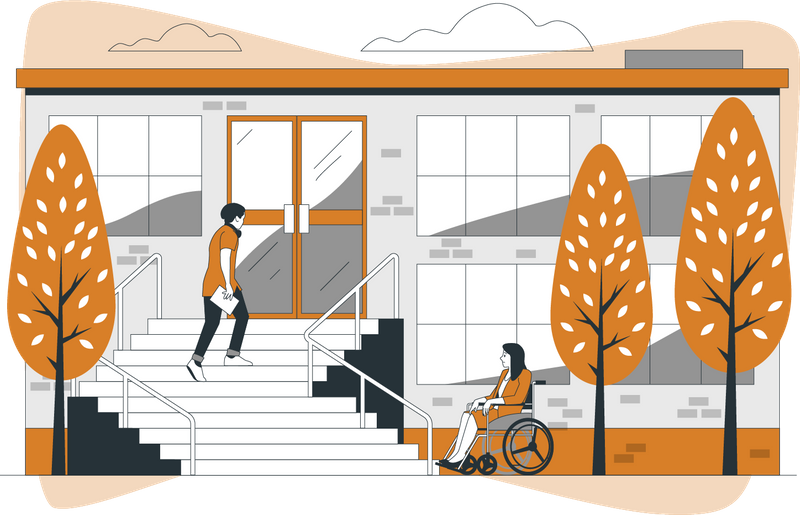

Example #1 — an architectural design that doesn't have accessibility in mind:

Imagine going to your new class, but there is no readily available ramp to get to the main front door with your wheelchair.

Instead, you find stairs and now have to look for a ramp or elevator around the building which could make you late and miss part of the lecture.

This isn't great because it takes longer time to reach the side ramp than the main stairs.

Accessible architectural design and learning design aren't that different.

These two types of design share similar goals, such as creating environments that accommodate the diverse needs of people in our community that we interact with.

Example #2 — learning design that does have accessibility in mind:

Imagine going to training as a learner with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and getting a handout of the class notes from your instructor at the beginning of class to follow along.

This is great because you might often have trouble paying attention to auditory lessons for a long period of time and you might miss some key spoken words.

Did you know?

Accessible learning design asks for your empathy. When we think about how things are designed from an accessibility lens, often many learners are left out. Think about a time during class where you felt invisible. How does that impact your motivation for going to this class? Did you feel like you belonged?

Accessible design requires empathy.

Image by storyset on Freepik and re-colored by Byte author.

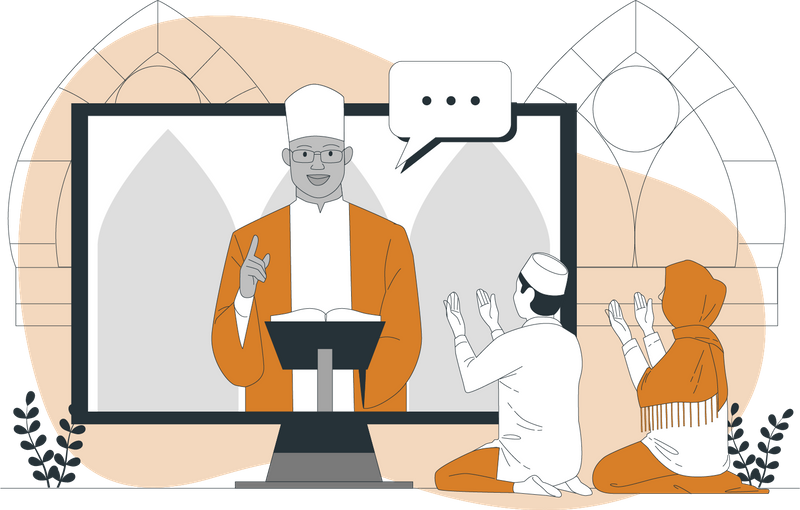

More than ever, it's common to encounter people with invisible disabilities.

...an invisible disability is a physical, mental or neurological condition that is not visible from the outside, yet can limit or challenge a person’s movements, senses, or activities.

— Invisible Disabilities Association

Regardless of someone's identity, including age, they may have a physical, mental, or neurological disability that can't be seen by just looking at them. It's very important to always reflect on our own biases and lean into empathy to seek understanding.

Image by storyset on Freepik and re-colored by Byte author.

Empathy allows you to understand learner barriers and limitations.

Empathy (noun): the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts, and experience of another.

Empathy is a tool that will allow you to be a better designer from the beginning of your design process by considering the abilities, disabilities, preferences, limits, culture, socioeconomic class, and life circumstances of all of your learners.

Image by storyset on Freepik and edited by Byte author.

Inclusive learning design with accessibility at the forefront reaches more learners.

...an inclusive design approach is one that perceives disability as a mismatch between our needs and the design features of a product, built environment, system or service.

Accessibility is always the right thing. It provides equitable learning experiences, reaches more learners, and benefits everyone, including you as an educator.

There are often legal requirements for accessibility compliance in design. Avoid re-designing a finished product without consulting an accessibility specialist in your learning organization!

Did you know?

Accessible design doesn't mainly focus on disability. Accessible design should also include people with different religions, culture, languages, financial situations, data limits, technologies, and more! Imagine living in the middle of nowhere and the only option is 3G connectivity on your low-tech phone within your budget. It may make loading images and experiencing the web slower and more selective.

What are common accessible learning design practices?

2. Use colors with high-contrast between text and background.

Visual ability is on a spectrum. Select text and background color mindfully. According to Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 AA, it's best to use images of text and text with a 4.5:1 contrast ratio with some exceptions, such as text in logos.

3. Use meaningful website link descriptions.

When designing and writing for accessibility, it's critical to think about how people that use screen readers, such as blind learners, experience your designs in class, especially for website links.

Not accessible:

Vague descriptions

Entire website URL links

Same text for different links

"Click here", "Learn more" or "Read this"

More accessible:

Longer descriptions

Meaningful word choice

Unique text for each link

More specific language

Quiz

Which of the following is a strong alternative text description for an image?

While all these alternative text descriptions may be relevant, providing more descriptive on the context, emotions, location, and who's in the image gives a more complete picture (literally) to individuals that rely on screen readers to read information aloud on the web. Providing a story to the image creates more meaningful alternative text! 🙂

What about information and visual layout in design?

Take Action

Did you know?

There are many resources and departments dedicated to accessible instructional design. If possible, check out your learning and teaching center at your work or other state or country departments that can provide more insights. Because this Byte is for educational purposes, not all accessible design practices were addressed.

This Byte has been authored by

Melissa Carrillo

Instructional Designer & Accessibility Specialist

Master of Science (MSc)