We trust numbers to tell the truth.

We're encouraged to let data drive what comes next.

Why not? They make studies sound solid and decisions seem smart.

But what if they miss what matters? The problem isn't the numbers.

It's mistaking numbers for knowledge that sends you off course.

Photo by Kenny Eliason on Unsplash

Photo by Kenny Eliason on UnsplashData literacy begins with knowing when to trust the numbers — and when to ask what they missed.

You know what it feels like to be reduced to a number:

A test score that didn't capture what you understood

Hours of sleep that ignored why you were awake

Years of experience that disqualified you before you even started

These numbers aren't wrong, but on their own, they're incomplete.

Self-reflection:

Think of a time someone judged you by a number. What did they miss?

What's the Big Idea?

Numbers can shape judgment in any setting. There's even a name for it.

A quantitative fallacy happens when we let numbers tell an incomplete story and make decisions as if we had the full picture.

Photo by Hartono Creative Studio on Unsplash

Photo by Hartono Creative Studio on UnsplashThe math might be correct, but the argument is flawed.

The argument leaves out critical context:

What was measured — and what wasn't

How data was defined — and by who

What got left out — and why

What assumptions were made — and whether they hold

But what we count isn't always what counts.

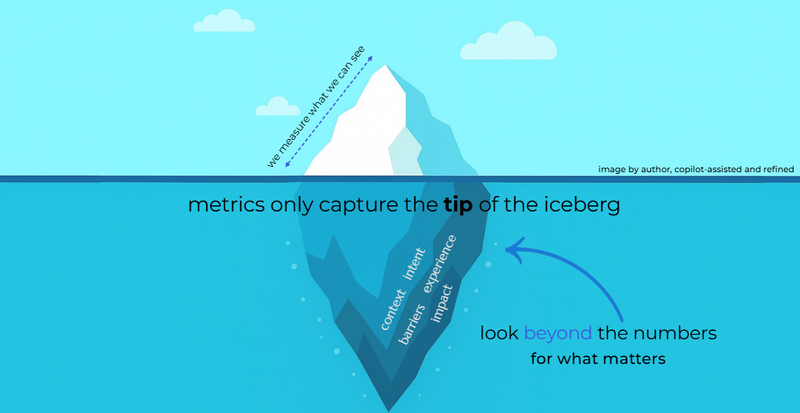

To hear an audio description of the image above, click play on the audio player below:

To hear an audio description of the image above, click play on the audio player below:

Numbers often leave out:

Intent: What someone meant to do → their goals, not their results

Context: Conditions that shaped their actions → what was possible in the moment

Experience: How it felt to live through it → the reality beyond the datapoint

Barriers: What stood in the way → the obstacles the numbers don't show

Impact: What changed as a result → the true effects, not just what was measured

The McNamara Fallacy: From Dangerous to Disastrous

When we mistake metrics for meaning, we set ourselves up for failure.

Quantitative fallacies use numbers to earn our trust while leaving out the rest of the story. They start with good intentions.

Measure what you can. Track progress. Take action.

Then, the thinking becomes something more dangerous:

"If something can’t be counted, it doesn’t count."

That’s the trap of the McNamara fallacy — one of the most dangerous forms of quantitative thinking.

Photo by Stephen Hui on Unsplash

Photo by Stephen Hui on UnsplashThe McNamara Progression of Thought

A fallacy is flawed reasoning that leads to wrong conclusions, even if the argument sounds logical. Daniel Yankelovich, a leading voice in public opinion research, described the McNamara fallacy in four escalating steps:

Measure what’s easy.

Disregard what’s hard to measure.

Assume the unmeasurable isn’t important.

Declare that the unmeasurable doesn’t exist.

Credit Example

When you borrow money through a credit card, lenders track how much of your available credit you're using as a percentage.

This is called credit utilization. If you have a $1,000 credit limit and you've spent $300, your utilization is 30%.

This percentage influences your credit score, which affects whether you can rent an apartment, get a car loan, or qualify for better interest rates.

Let's see what happens when utilization becomes the measure of financial responsibility. Here's how the McNamara fallacy unfolds:

Measure what's easy. Track credit utilization as a percentage.

Disregard what's hard to measure. Overlook actual ability to repay, savings on hand, and why the balance exists.

Assume the unmeasurable isn't important. Decide that credit utilization measures true financial responsibility.

Declare that the unmeasurable doesn’t exist. Treat utilization as the sole deciding factor and claim it measures "creditworthiness".

Look Beyond Numbers

Following this logic creates a distorted outcome.

A borrower who uses $200 on a $500 limit (40% utilization) for a one-time emergency gets flagged as high-risk. But someone carrying $10,000 on a $50,000 limit (20% utilization) looks more responsible — even if they owe 50 times more.

Ask: "Are we measuring what matters, or just what's easy?"

Quiz

We track the number of clicks a search result gets to measure satisfaction but ignore whether users found what they needed. Which step does this best describe?

Did you know?

The Proxy Fallacy: Measure What's Easy, Miss What Matters

Intent is the first thing that metrics flatten.

We measure what people did, not what they meant to do.

That's how we mistake effort for outcomes and goals for results.

The proxy fallacy happens when we measure something we can track (the proxy) and assume it tells us something we want to know without checking if it actually captures what matters.

The Proxy: 10,000 Steps

Walking 10,000 steps a day is often treated as a universal benchmark for health and wellness. It has become shorthand for "being active". The fallacy arises when people assume that hitting 10,000 steps means they are “healthy”, regardless of intensity, diet, or other lifestyle factors.

Photo by James Orr on Unsplash

Photo by James Orr on UnsplashWhy Steps are a Weak Proxy: The Misses

Intent → We want to measure health, but we're counting steps.

Context → The 10,000 number is marketing, not science.

Experience → Steps can't tell if movement is beneficial towards health goals.

Barriers → Steps assume equal access to safe movement (but ignore injuries, physical disabilities, and mobility limitations).

Impact → Steps track motion — not whether your health actually improved.

When the proxy is weak, hitting the target doesn't mean you've reached your goal.

Subscribe for more quick bites of learning delivered to your inbox.

Unsubscribe anytime. No spam. 🙂

What Else Do the Numbers Tell Us?

Next time data makes a claim:

Next time data makes a claim:

Pause.

Think:

What story are the numbers not telling?

Reflect on the "why?" and "how?" not just "how much?"

Remember:

Metrics show outputs (the immediate results a system produces), but useful measures ask what drives outputs.

Consider both quantitative and qualitative measures.

Example: 10,000 Steps a Day

To measure what matters, you need to account for more than movement alone. Prescribing 10,000 steps is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

To hear an audio description of the image above, click play on the audio player below:

To hear an audio description of the image above, click play on the audio player below:

Wellness goes beyond steps.

Here is how the bigger picture unfolds:

Mood shapes effort and outcomes.

Rest and recovery fuel resilience.

Energy and capacity fluctuate with resources.

Recovery and repair are just as important as exertion.

Intentional choices define meaning, not just actions.

Endurance and sustainability matter more in the long run.

Capacity and readiness determine what’s possible in the first place.

Take Action

You've seen how metrics have blind spots.

You know what truths to look for beneath the surface.

When you work with data, remember what you learned here.

Photo by Deng Xiang on Unsplash

Photo by Deng Xiang on UnsplashYour feedback matters to us.

This Byte helped me better understand the topic.